Why did the 80s look that way?

Everything is pastiche

As I pointed out a couple of weeks ago, people were throwing 80s theme parties almost as soon as the decade was over, and the 80s nostalgia wave has continued with minimal interruption ever since. This phenomenon hasn’t happened for any other decade. Attempts at making “90s nostalgia” a pop phenomenon feel forced, and “Y2K” trends even more so. You can throw a Roaring Twenties party, but it pretty much stops there. Nothing can compare to the success of Vh1’s I Love the 80s (2002) or Stranger Things, season 3 (2016). And so much of what’s remembered about the 80s is visual style specifically. What is it about the 80s that makes this the case?

The look of the 80s is, for starters, probably best represented by the Memphis Group, founded in 1980 in Milan by Ettore Sottssas. Memphis is known for furniture mainly using plastic laminates in bold colors and patterns—Sottssas would eventually design showrooms for the clothing brand Esprit in the Memphis style. (Curbed has a helpful primer.)

The curator of a recent retrospective in Bordeaux, Jean Blanchaert, offers some political context:1

The 1970s were nightmarish: the Red Brigade, economic and financial crises, strained democratic institutions. Society was overrun by a sense of dread and a bleak outlook. Memphis burst on the scene like a speeding train.

But there is some confusion as to the precise influence of Memphis given that it arrived in line with new wave music and a number of other artistic trends of the late 70s and early 80s. (The graphic designer Dan Friedman’s apartment from the era would seem to be a notable reference point.) And the group had disbanded within a few years. Blanchaert quotes Ettore Sottsass:

"Powerful ideas," said Sottsass, "don't evolve. They are what they are, they descend like lightning bolts. They're here one minute, and then they're gone the next."

In 1981, MTV was launched. The launch of the network featured a depiction of the moon landing, with a flag of the MTV logo being planted. The logo stays fixed in place while flashing between bold colors and patterns, all highly suggestive of Memphis and related styles.

One particular color combination is a sort of hot pink with green or teal. These colors alone are highly associated with the idea of an 80s look. They appear in clothing, probably suggested by fitness trends. You’ll encounter them immediately if you search online for “80s outfit” or “80s design.” Pink and teal appear together in the title card for Miami Vice, which references the art deco lettering of Miami. The show began airing in 1984 and is well attested as an influence on 80s style and fashion. (And undoubtedly the decade’s uniquely campy reputation.) The two colors are complementary, and relatively pleasing—but also bold, even harsh. They are a deliberate, intentional palette.

In the context of MTV, pink and green read as a reference to punk, specifically the album covers for Never Mind the Bollocks and London Calling. If this seems to place these colors firmly in the zeitgeist of the end of the 1970s, it’s worth remembering that London Calling was an explicit reference to the debut album of Elvis Presley. But we can trace the story back even further than that.

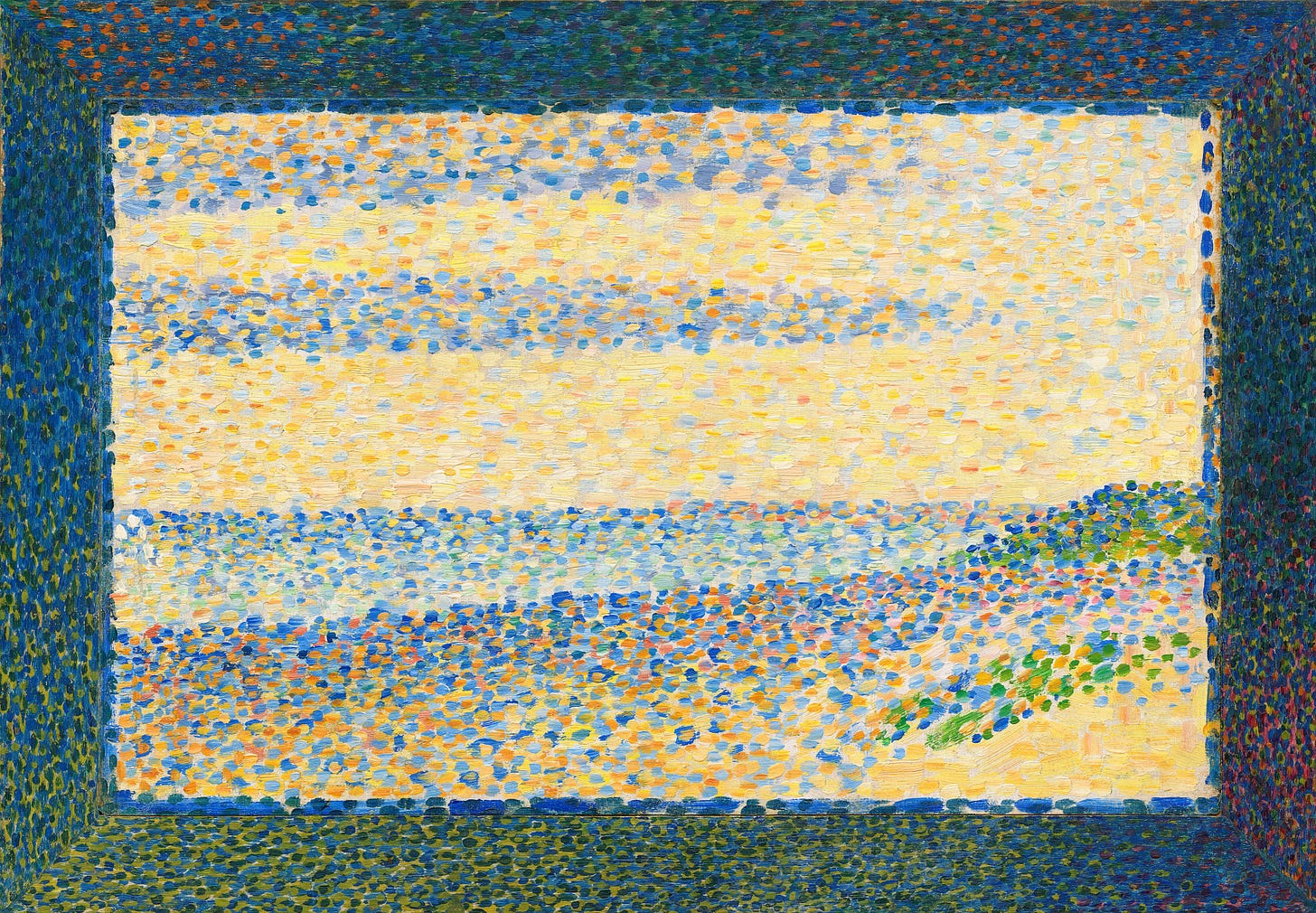

In 1905 a handful of artists exhibited new paintings at the Salon d’Automne in Paris, in a style that would be dubbed Fauvism. Notably, the National Gallery of Art in the US calls it the “first avant-garde wave of the twentieth century.” The most distinctive feature is the use of bold, saturated colors, or perhaps more to the point, exaggerated or non-naturalistic colors. Pink and green were a routine combination for the Fauves.

The parallels to the later Memphis are numerous. A group of artists, a group exhibition, a seemingly sudden avant garde movement largely known by its visual loudness (and an odd name that always has to be explained). Fauvism was also short-lived; the preface to a 1981 book on Fauvism,2 translated from the French, refers to it as a “lightning phenomenon.” Within a decade of the 1905 show cubism was introduced, and following that the rapid development of modernist art and design, which among other things would inspire a focus on novel materials and stark geometric form that would carry across the century.

The use of garish color palettes continued apace, but the medium wasn’t strictly in painting. Notably in the 1930s—right around the time Miami’s art deco buildings were being put up—Elsa Schiaparelli debuted clothing in “shocking pink,” a color like the hot pinks and magentas that would later be seen as almost unique to 80s style.

The social disruption and austerity brought on by World War II seems to some degree have disrupted these cultural progressions and stirred a cultural conservatism. (By 1947 Dior introduced his New Look, perhaps the most obvious evidence of a conservative strain in immediate postwar culture.)

But even if they had quieted down, the technological, artistic, and cultural change of the first half of the century were quickly revving up again. (By 1949, John Lautner had designed the Googie’s Coffee Shop, namesake to the space-age Googie style of architecture. It’s difficult not to see this as a precursor to Memphis, particularly since from what I can gather from photos it even included terrazzo flooring.)

In 1954 the Times ran an article suggesting that the fifties might be remembered as “the Age of Color.” The article quotes a “color consultant” who had conducted a survey for Monsanto’s Plastics Division and found that “in the last few months pink has had a striking increase in popularity with a heavy demand being noted for this color in kitchen cabinets, plumbing fixtures, wall tile and housewares.”

The fifties were also a time of growing youth subcultures and countercultures, which drew the attention of the media and were instantly commodified. Rock and roll and beat culture were succeeded in the 60s by hippies, the beginnings of punk, the pop art movement. Warhol produced screen prints of Marilyn Monroe, in pink and green among other vibrant combinations. Push Pin was creating classic and distinctive works of graphic design; Frank Stella would start moving out of minimalism. Glam and punk developed over the course of the 70s, with disco, new wave, and hip hop. The postmodern turn in architecture and interior design bore a conspicuous, almost parodical use of industrial styles and shapes. (The Centre Pompidou, for example, was constructed by 1977.) Plastic housewares in bright colors were produced all the way through.

So if the self-consciously bold colors and patterns of the 80s came as a shock, a sensation, they were also part of a long lineage. I wonder whether the attention to these styles, and their reproduction, doesn’t have something to do with a culture that in some sense wanted a sensation, as the curator’s quote above suggests. (And this is to say nothing of an industry with a lot of plastic to sell.) Maybe the almost comic shapes of Memphis, which in some sense translated pre-existing graphic styles into a very immediate physical form, had the effect of saying the punchline everybody was waiting for. The 20th century was an explosion of industry, which led to an explosion of artificial color, so now it was time for spaces people inhabit—at least the spaces relatively well-off TV-watching people inhabit—to become a literal embodiment of those changes.

There are still plenty of questions to ask about our selective attention, and about coincidence. The explosion of cable TV and the VCR in the 80s helped make it a time of rapid movement and repetition of information. Archival media make artistic developments of the past seem more uniform, focused, and ubiquitous than they were. And they make the present seem realer than the past.

The assumption of progress and of the avant garde, often symbolized through color, has likewise created an impression of the present as somehow truer than the past, and of the past as always quaint. This is itself a quaint idea. As artistic styles have seemingly become increasingly referential they’ve seemingly become non-philosophical, and even less optimistic. (To say nothing of becoming detached from history.) In an increasingly media-driven culture I wonder whether there can be another “lightning” art movement, or what effect it will have.

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, you can let me know by hitting the like button, usually at the bottom of the post.

Memphis Plastic Field, 2019. Edited by Constance Rubini, published by Éditions Norma.

Fauvism: Origins and development, 1981, by Marcel Giry. Preface by René Jullian. Translated by Helga Harrison, published in English in 1982 by Alpine Fine Arts Collection.